Rae Armantrout

First, I should say that neither of these drafts is really the first. My poems always start in blank- books with a few illegible scribbles. I only take a poem to the computer when I suspect I have a proverbial “fish on the hook.”

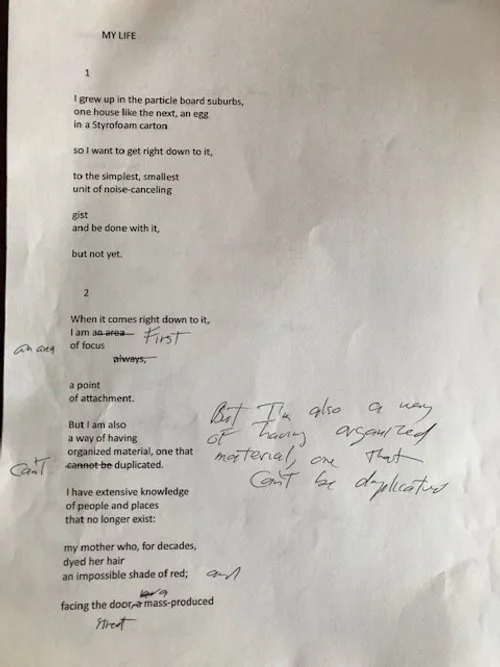

I can see three different origins here. First, you’ll notice that the first four stanzas of the second part deal not so much with who I am as with what a self is. This is a long-standing preoccupation of mine. Maybe it started there. Then again, the lines about the pear tree “twinkling” could have come first. That tree’s outside my window and often draws my attention. Finally, I was asking myself why my poems aren’t more personal. Section one addresses that question indirectly. I decide to “go there” when I bring in my mother -- her hair dye and décor.

I was surprised when I found “My Bio” and read the last section. It clearly doesn’t belong there. I have to watch out for including things I find interesting but which are too far away from the poem’s center of gravity.

Over the course of these versions, I struggled with the seventh (or sixth) line in the first part— the single word line. It went from being “truth,” to “gist,” to “hum.” “Truth” was always a kind of place-holder. I knew that abstraction was too ponderous. So maybe not truth, but “gist.” Gist is like essence, but without the metaphysical baggage. Still, I wasn’t quite satisfied. For one thing, what does it have to do with the phrase “noise-canceling?” Eventually, I moved “gist” to the title position and came up with “hum.” If you want to get down the gist of something quickly, there’s probably a lot you want to block out so you can relax with your white noise.

Another problem area was in the third stanza of the second part. I don’t know why I was using the past or past-perfect tenses in the earlier versions. I knew it was awkward. In this case I consulted a friend who suggested putting it in the present tense. It sounds obvious now. When I’m stuck, I find it helpful to consult a friend. You don’t have to let them take over the poem. For instance, a different friend suggested I should take out the painting on my mother’s wall, but I chose to keep it.

In the final section, I changed “coldly” to “coolly” because I wanted the twinkling light on the leaves to sound pleasant. The tree’s burgundy leaves echo my mother’s red hair. Burgundy is a cooler version of red. It doesn’t come at you like wild horses. In version two I went off track briefly when I called the leaves “mass-produced.” That’s the wrong tone. Lastly, I decided to break the line after “burgundy.” I wanted it to sound like I was ordering wine. Cavalier. The speaker seems to think she can have whatever she chooses “forever” “instead.” But leaves fall.

•

“Gist” appeared in the February 5, 2024 issue of The New Yorker.

< draft >

MY BIO

I grew up in the particle board suburbs, one house like the next,

an egg in a carton.

So I want to get right down to it,

to the simplest, smallest

kernel of noise-canceling

truth

and be done.

*

But when it comes right down to it,

I am area

of focus

always.

A point

of attachment.

Or I was a way

of having organized material.

I have extensive knowledge

of persons who do not exist.

Of my mother who

for decades

dyed her hair the same

impossible red.

*

of this November pear tree,

coldly twinkling

if I get to choose.

I don’t.

*

I clean up nicely.

I throw myself in bed

and come up

stretching,

a green question mark.

< REVISION >

MY LIFE

< final version >

gist

1

I grew up in the particle board suburbs,

one house like the next, an egg

in a Styrofoam carton

so I like to get right down to it,

to the smallest

unit of noise-canceling

hum

and be done with it,

but not yet.

2

I am first

an area of focus,

a point

of attachment,

but I am also

a way of arranging

material—

one that can’t

be replicated.

I have extensive knowledge

of people who don’t exist:

my mother who, for decades,

dyed her hair

an impossible shade of red

and who had, facing the door,

a popular painting

of wild horses.

3

Can I have the burgundy

leaves of this old

November pear tree

coolly twinkling

forever instead?

Omotara James

A poem announces itself at its beginning and its end. The body of the poem is the instruction of how the poem should be read. My poem is finished when my spirit has closed the gap my intellect has yet to cross. The spirit of the poem creates a chasm or a river, to which one repeatedly returns for a different answer to the same question. The ancient proverb, a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush suggests that it is more prudent to value what one already possesses than to risk it on the chance of attaining more. On revision, I find the opposite to be true. I choose to revise towards the truth beyond reach. I am most interested in the lyric comprehension that allows me to understand and feel what is true before the words bridge the gap.

Because I knew at the outset that I wished to tell a story, I began the poem in quatrains: a reliable vehicle for narrative. During edits, I decided the enjambment of the line breaks distracted from the lyric. The breaks make the poem feel too self-reflexive. The longer lines make the poetry less obvious. In the first draft, the poem reaches toward a surreal realism that could not be attained with the quatrain. The shorter lines imbue the language with a syntax that feels too spell-like. I desired the poem to invoke a conjuring, not to conjure. Therefore, I’ve extended the line so one’s breath runs short. This creates greater urgency travelling to the end of the line as the poem is spoken. Always when revising poems, I read the work aloud, a hack for regulating its music. This process grounds the poem in the oral tradition of song. Lastly, the poem flashes back from the present moment of the speaker’s life to previous moments before she was born, which requires a physically wider box on the page. There's no other way for me to explain that LOL.

The poem concerns itself with the intersection between poetry and folklore. It interrogates the liminal space between the known and the unknown. The fodder for the poem comes from Follow the Drinking Gourd, popularized by Black American singer-songwriter Richie Havens in 1991. The folklore behind this song is located within the origins of the Underground Railroad, which itself is a phrase loaded with metaphor, agency, and hope. The drinking gourd metaphor refers to the Big Dipper. The discourse between astronomy, astrology, slavery, and liberation presents a sublime canvas for poetry, laden with science, culture, and history. Furthermore, the folklore behind the lyrics of this African American folk song connects the figurative stops of the Underground Railroad to the covert, pastoral references relayed to enslaved Black people journeying toward freedom.

While scholars have debated verbiage associated with the railroad stops in the song, dissent does not challenge the magic and tenacious spirit of the real-life people who created the Underground Railroad network, through which many enslaved people journeyed to freedom.

This poem was commissioned for the folio Black Hauntology, curated by Phillip B Williams, for the Yale Review. The instructions for the prompt of the poem follow:

1. How does your work communicate with the dead?

2. What have you learned about your artistry and craft from ghosts, disembodied voices, the guiding hand that casts no reflection in the mirror but that you feel on your shoulder as you make?

3. “What does any of this talk about spirit in art have to do with loving Black people?”

4. Who do you honor on the other side? Who watches over you?

Phillip poses powerful questions. During revision, I decided there was more to offer the first question. I can trace this emphasis to the revised ending of the poem. This was the most powerful question and it felt just to answer it last, from the volta onward.

The penultimate stanza performs a lot of work, and to my ear, allows the ending to feel earned. Earned and open.

A version of this poem implementing the structure of the original draft and the language of the second draft was first published in the Yale Review. The final version of the poem appears in my debut collection, Song of My Softening, which is the revised version on the right.

< draft 1 >

Ars Diaspora under Capitalism with Drinking Gourd

(after Richie Havens)

As morning unspools new glory across the earth,

it rescinds an inch,

at least, of borrowed light. Today

those who wake heavy and heaved

beneath the lowest rung of love, press

their ears to the first quail calls of sky.

I ride the train north, underground, having hollowed

the daily enemy of its gourd-mouthed pride.

My father’s gaze across my flesh, measures the distance

between my life and the grandfather I never met on Earth.

My father’s father, disembodied by time, visited him

in Trinidad, the evening before I arrived.

The riverbank of my father’s tide, surges sweet

with sorrow, as the Caroni river runs through the sugar belt.

He recalls the dream’s wordless joy: granddad smiling

ahead of me. We are headed into New York City together,

rare luxury to dwindle time, languorously. Under my gaze,

dad dips back into memory from his vinyl subway seat,

as if on holiday, pouring out another ladle of rum punch.

In this moment I see every celebration day we spent apart,

Projected onto his dappled brown, black face. Stripes of shadow

conjure this slideshow, as we emerge from tunnel to light.

He says granddad came to tell him I was coming,

each dark twinkle of his eye, a dead tree summoning.

Dad says the words from the quarrel last night

between my mother and I, what we spoke yesterday,

has already traveled ahead of us

between two hills, where love waits.

He says, our dead return when the flesh is weak

to remind us and warn against—

each beginning and ending,

a portal too dangerous to ignore.

Tonight, midsummer sits across the unset table

of the moon, the meek yet to inherit

the earth, the suffering yet to end

in peace. Upon me, the measureless distance

between words we want to believe and what

the spirit already knows. I call and call and call

and call and call and call and call.

When speaking to the dead, I hum the melody of the body

until the little river joins the great big river, almost always

losing my way. Dark, my most loyal friend,

sings follow the drinking gourd.

< final version >

Ars Diaspora with Drinking GourD

After Richie Havens

Eugenia Leigh

I write to uncover. To excavate. Every draft begins without lineation, and I commit to freewriting to keep the brain faucet on, to flush out the murky thoughts until more drinkable thoughts run clear. This means a good portion of what I’ve written will be trash. Filler thoughts or, worse, lies. I lie to myself a lot. Possibly to protect myself from truer thoughts I’m not yet ready to face. My mind also hosts many other people’s lies.

I run an internal lie detector over every line throughout the revision process, but especially after that first freewrite. I evaluate the draft for inaccuracies and evasions, but I also ask: am I putting on a “poet’s voice” or somebody else’s voice? Which lines are my voice? I also attempt to catch when I’m trying too hard to “write a poem.” Lines such as “How to mute the wasps fruiting within me” or “Am I violent? Am I sugar?” set off my bullshit detector. Do these lines reveal something or are they simply lovely and poem-y?

When I unearth a surprising line with authentic emotional clarity—such as “But the thing I miss most about hell is prayer”—I start a new draft with that line as the anchor. But because I cut so much from each freewrite, one draft rarely contains enough scraps to make a poem. Conversely, because every freewrite comes from my same obsessive brain, sometimes thoughts along the same train appear in multiple documents. So when I have my anchor line, I often search through older, unresolved drafts for moments that resonate with this line. Once I located “I want answers from the maker of figs” in a months-old document, I saw the vague shape of a poem asking to be sculpted from these two blocks of text.

< DRAFT 1 >

The Wisdom of Our Twisted Earth

Sycamore figs ripen only when struck. The way a bruise may sweeten a child toward empathy. I want answers from the maker of figs. How to mute the wasps fruiting within me. How to soften with age. Studies say the desire to maim animals burgeons in those who’ve endured abuse. Also, the desire to save. Am I violent? Am I sugar? The news is foul with the fruitless, and we all love someone snared inside some hellish nebula. What I’m saying is, not all the marred are redeemed, and I demand to know why. Who seeded our ugly earth and missed them. Why, struck and struck, their bitterness remains.

Out of the Mud

We are either on the road or in the mud, a roommate once said—after all our roads had vanished, after we’d ravaged ourselves in search of crags to end from, after we’d filled plastic bottles with vodka to chug in the parking lot of a pancake house and cry, but before she patched up homeless patients, before I revised a single line, before we married men nothing like our fathers. We are, it seems, out of the mud. Go on and tell it to the mountain. But the thing I miss most about hell is prayer. We prayed like everyone we loved was on fire. We’d sit on the carpet she paid for in front of the red futon I slept on, and we’d scream. I would shut my eyes and watch my father’s face melt into something lovable. I would watch the planet shaking like a child stricken with joy. And the bright and sizzling blob I knew to be God injected itself into every locked closet I thought I’d endured alone. Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven. On the road, I am not wrecked enough to ask for a kingdom. I’ve cobbled together a passable existence. When my husband asks me to pray for our meal, I say no. I can’t stomach thanking the Maker of the Universe for the peas on my plate.

< final version >

what i miss most about hell

is prayer.

I’d pack a plastic bottle

with vodka, drive

to the crag of my life—

the parking lot of a pancake house—

and scream. I prayed

like everyone I loved was on fire.

The bright, violet blob

I called God

would forgive the atrocities

roared in ethanol

while I’d shake like a dog

demanding answers

from the maker of figs:

why the sycamore fruit

sweetens only when bruised,

the way a fist will

ripen a child.

_______

“What I Miss Most About Hell” from Bianca (c) 2023 by Eugenia Leigh. Appears with permission of Four Way Books. All rights reserved.

Iain Haley Pollock

The narratives could not hold. My lived experience of COVID lockdown resisted the arcs of dramatic tension, intensification, and resolution. The warping of time during those months led to a haze in my memory that wouldn’t burn off. I couldn’t locate the specific, tangible details that lay at the foundation of my narrative poems. Absent these details and with that period so dissolute in my mind, after rounds of revision, I couldn’t get the narrative logic of these COVID poems to hang together.

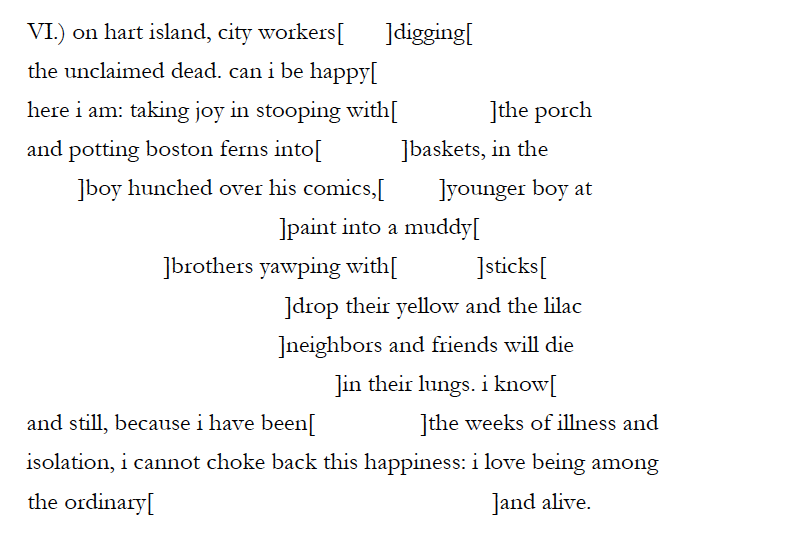

Separately, I admire Sappho’s fragments in Anne Carson’s translation, If Not, Winter. The imaginative possibilities of the poems seem amplified in the lacunae. While many poets have influenced my poetics and my technique, when I stumble into a particular and intractable poetic thicket, I’m not in the practice of consciously turning to other writers for direction and usually wander until I find a path that brings me out of the brush. For this series of poems, however, realizing that my memories of the days of anxiety, Zoom, and social distancing had collected into a disjointed assemblage, I experimented with a fragmentary approach adapted from Carson’s renderings of Sappho.

I turned each narrative poem into a text block then redacted my own work according to rules—such as mirroring Sappho’s forms and including at least part of a recurring line that appears in each poem—rules that soon dissipated as more improvisatory approaches suggested themselves. Chiseling down the text blocks, I found my language recombining into new, strange, and unintended syntactic structures. That some of these structures made sense without quite making sense reflected my experience and memory of the “weeks of illness and isolation.” As the new syntax created its own meaning, I hoped that the poem’s bracketed “lacks”—as Carson calls them in Sappho—would create space for readers’ imaginative play. To the extent that COVID was a shared phenomenon, I wondered if readers might understand the experiences I gestured toward but excised and might fill the lacks with versions of their own narratives, similar but different than those intended in my original drafts. These narratives still could not hold, in a logical sense, but now they better reproduced the indelible fracture of my COVID existence.

< draft 1 >

Of Marks & Lacks (drafts)

III.) a worker grips a pesticide jug filled with disinfectant and sprays down carts after customers wheel them back curbside. his colleague walks down the line that wraps around the store’s corner, handing out plastic gloves to us who wait for food six feet from the bodies to front and back. twenty deep i started this shuffle to the grocer’s door—a long line but not desperate. and to occupy me: the norway and silver maples on the surrounding ridges coming into bud, their red swell all the more vivid against a sky that glowers a color somewhere between soviet housing block and raw steel. new leaves just pushing out, the trees allow clear sight lines to the taconic, to the trickle of cars headed south toward the city at what would have been, three weeks ago, morning rush hour, and to the lone house balanced on the hillside above the parkway. two spots ahead of me, a woman wears bright blue surgical gloves and a white dust mask fit for a demolition job. she’s been looking over her shoulder at a black toyota and, from time to time, waving. while we slouch forward, her husband unpacks their toddler from the backseat and keeping the girl a distance from the line, lets her run gleeful circles around an eroding tree bed, its mulch washed away over the winter. with her daughter outside the car, the woman waves across the lot as though she’ll never see the child again. three weeks ago, my eyes would have rolled at any one of these: the gloves, the mask, the histrionic waving. today, amid the weeks of illness and isolation, they stay fixed on the hillside. how long before nature runs its course, and the house surrounded by burgeoning maples gives way to gravity, loses its footing, and apex to foundation comes sliding, in a sudden thunder, down the slope?

VI.) on hart island, city workers are digging trenches for the unclaimed dead. can i be happy in times like these? but here i am: taking joy in stooping with naomi on the porch and potting boston ferns into hanging baskets, in the older boy hunched over his comics, in the younger boy at his easel slathering poster paint into a muddy brown. joy, later, in these brothers yawping with raised sticks in the yard, where the forsythia drop their yellow and the lilac burgeon into their color. neighbors and friends will die today with a tightness crushing in their lungs. i know this and still, because I have been amid these weeks of illness and isolation, i cannot choke back this happiness: i love being among the living and alive.

VIII.) amid the weeks of illness and isolation, the younger boy skulks nightly into our bed, climbs over the escarpment of his mother, and wedges himself into the narrow valley between her body and mine. in winter turning spring, light not yet limning east and ridge-line, i’d gather him across my forearms, blunder down the hall, and drop him back into his bed. wrapped in a frog blanket, his since birth, he’d shut-eye a few more hours, then back to our room and mattress. by early summer, i’d given up gathering him, let him lie with us, no matter the state of sky and light. on his most restless nights, he’d wrench his diminutive frame perpendicular to ours, his hard head pillowed on his mother’s waist, his feet slung over my hips, making of our bodies a crude letter, the h i tried to teach him during the day to recognize and, in his unsteady scrawl, to write. the weight of even his small calves pushed down onto my socket and joint kept me wandering in the borderlands of sleep. or just plain awake. awake and hearing the trundle and horn-blare of the first commuter trains hauling near-empty cars into the proud but intubated city.

< final version >

Of Marks & Lacks

[Sections III., VI., VIII.]