Tim Seibles

Initially, each of these poems began with an opening line that seemed to come from out of nowhere. From that point, I began to write what seemed to come next -- whatever felt organic to that first utterance.

As always, my revision process involves slow but steady editing and adding to the poem's body. Clarity is the thing I'm after; I tell my students all the time "it doesn't matter how brilliant an idea is if it can't be understood." So, after the first rush of words, I try to figure out what the essential news of the poem is.

Then, the process becomes one of searching for fresh language and clearing away all that is merely muttering and stuttering. Ideally, one is left with something readable and memorable.

*

Photo credit: Jennifer Fish

turn it up

AND YET

turn it up

Brothaz in gangs, man, they don’ see no other way.

--Jeff Bryant

Hey, DJ --r un that back

--Ludacris

Days when I think I might

live forever: sunlight standing on the corner,

brim bent to one side, nothing

to remember—

the breeze changing shape: one leaf, then

another a whole branch smiling.

What I want to say

is this: you do not have

to die—you do not

have to die with your eyes

broken and blood burning

your fists. Brothaz,

today is a door,

the hour, still open.

Though the trap has been set,

though the graves

keep calling, we do not have to listen.

Look:

after all these years, Time

still lives down around the way

across from the schoolyard,

waiting for everybody

to come over: the plates are hot,

the bass is bangin’—the DJ

won’t, d-d-don’t stop.

Untie your hands.

Turn up your heart.

AND YET

the poem remains

unafraid: a black Pegasus

tattooed on its

bare chest.

Do whatever you want!

the poem taunts, as people

steady the scaffold

and test the noose.

It’s dawn.

The poem’s been

awake for hours

wondering why

it has to be

this way, when once

there was song

and so much promise.

Do your worst,

the poem laughs, flexing

its pecs so the black wings

flap and the poem begins

to rise, begins

to see itself

far above the mob,

far from all the trouble—

objective, detached—

like a coffee shop:

citizens coming

with no dirty looks,

no axes to grind,

just wanting

something to propel them

into the relentless

day with clear sight

and a thumping heart.

Just get your coffee

and get out! the poem shouts

the sun leering now,

elbowing the clouds.

Jacob Saenz

The origin of this poem began in the summer of 1999. At the time, I was 17 and taking a poetry workshop course at Columbia College Chicago as part of their High School Summer Institute program. I rode the Blue Line (now the Pink Line) into the south loop for class and encountered the gangbanger in the poem twice, as “Frustration: Off Chest” indicates. The original draft is really just a rant addressed to the gangbanger specifically but the anger of the poem is born out of multiple incidents with gangs. Growing up, I guess I looked the part of a gangbanger so I would get questioned and checked a lot about my gang affiliation, which was none despite the many gangs in my neighborhood. I grew tired and frustrated with those encounters and took it out on the page. For the workshop, I’d bring in a poem in a different font every week and, that week, I was really feeling the Bold Impact or some such font. The font seemed to fit the tone of the poem.

Years later, after enrolling in the Poetry program at CCC, I revisited the poem with new skills and technique I had learned. I wanted to slow down one of the encounters with the gangbanger in the poem and give him more voice. I focused on sound, rhyme, and line breaks as well as metaphor. The bunny in “Blue Line Incident” is a reference of the symbol used by Two-Six Nation but it also works for showing how helpless and scared I felt at the time. I cut down a lot of the curse words used in the original but I still wanted to maintain some of the anger and frustration I felt at the time, hence the violent fantasy. I didn’t intend to have it end as a “pen is mightier than the sword” motif but it seems to fit the poem.

*

“Blue Line Incident” originally appeared in RHINO magazine.

blue line incident

He was just some coked-out,

crazed King w/crooked teeth

& a tear drop forever falling,

fading from his left eye, peddling

crack to passengers or crackheads

passing as passengers on a train

chugging from Chicago to Cicero,

from the Loop through K-Town:

Kedzie, Kostner, Kildare.

I was just a brown boy in a brown shirt,

head shaven w/fuzz on my chin,

staring at treetops & rooftops

seated in a pair of beige shorts:

a badge of possibility—a Bunny

let loose from 26th street,

hopping my way home, hoping

not to get shot, stop after stop.

But a ‘banger I wasn’t & he wasn’t

buying it, sat across the aisle from me:

Do you smoke crack?

Hey, who you ride wit’?

Are you a D’?

Let me see—throw it down then.

I hesitate then fork three fingers down

then boast about my block,

a recent branch in the Kings growing tree;

the boys of 15th and 51st, I say,

they’re my boys, my friends.

I was fishing for a life-

saver & he took, hooked him in

& had him say goodbye like we was boys

& shit when really I should’ve

gutted that fuck w/the tip

of my blue ballpoint.

Janine Joseph

Sometimes, the more I want a poem to proceed, the more the process begins to feel like an interrogation or immigration interview. I respond by pivoting on the page and writing myself into a corner or through an easy exit. I know when I’ve done this because the poem will suddenly claim to have nothing more to say, though the document will remain open on my computer and I will mull lines aloud while I go about my day.

When I draft, I have to be cognizant of this impulse to turn away or show myself out and how it tricks me into thinking the work of the poem is done. I move away the lines or sentences that lead me into insincerity as they appear and approach the material again. My drafts are full of pages of these bob-and-weaves, misfires, false starts, diversions, and dead ends. Honing requires patience on my part—and this poem in particular had to trust me.

*

This poem first appeared in Connotation Press (John Hoppenthaler’s “Poetry Congeries”)

TAGO NG TAGO (TNT)

He was petrified of them, though I can’t say,

because of what we did,

that he was gullible. Once, my cousins snaked

the hallway and waited for him

to power on the lights. He sprinted from their house

to ours, where we were as cold-blooded,

shrieking, Watch out! from our open door.

Wall cavities, attics, and crawl spaces made him

wet his pants. Anywhere the grass moved

or seemed to move. Our poor cousin, we’d say

and, Kawawa naman when he laid low

beneath the bottom bunk, waiting

to surprise his mother who we knew

was not his mother saving up in the States,

but a family friend with her hand out to him.

He stood quietly, his shirt ironed

and tucked, a good, good boy in line

with his stand-in at the passport office,

while we were vigilant about saying nothing

that might set him off. Be a good, good

girl, they said, and held me back

when I stepped out of the car. I clamped

my eyes shut. I could catch conjunctivitis

from making eye contact. They pointed

at my throat, bobbing, and said disclosing

too much would make it explode.

TAGO NG TAGO (TNT)

Because my cousins kept telling him to watch out,

my cousin was terrified of wall cavities, attics,

and crawl spaces—anywhere snakes could build a den.

Firewood piles, banks strewn with garbage,

and dilapidated tires made him wet his pants,

though I can’t say, because of what we did,

that he was gullible. Once, my cousins, thrilled

with rubber fakes, snaked the hallway

and waited for him to power on the lights.

He scrambled onto his bike and sprinted

from their house to ours, where we were no better,

shrieking Watch out! as mambas, like concertinas,

extended from our open door. Our poor cousin,

we’d say. And Kawawa naman when he laid low

beneath the bottom bunk, waiting to jump

Surprise! at his “mother” who we knew

was not his mother. I believed them once and one time

hid under the bunk with my fingers clamping

my eyes shut when they said I could catch conjunctivitis

just by making eye contact—but even I

knew that their mother was saving up in the States

and that the woman holding her hand out

to him was a family friend. But he stood quietly,

his shirt ironed and tucked, a good, good boy

in line with his stand-in mother at the passport office,

while we were vigilant about saying nothing

that might set him off. Just minutes after

we stepped out of the car, my cousins held

my head back, pointed at my Eve’s apple, the bobbing

arch of my throat, and said disclosing

too much would make it explode.

with the woman

standing in as his mother and we were careful

to not say anything that might set him off.

I was the youngest, the baby of the family

and we

tucked in his shirt and waited quietly

You have to be careful, they said, to not say anything

that might set him off.

coming

reaching her hand out to my cousin was a

was making a living in the States, saving up

to one day fly them all and that the woman

I’d seen her

eyes closed when my brothers said I could catch

pink eye

but even I knew their mother

lived in the States.

Their mother, even I knew, because I’d seen her,

crying like the baby

of the family. Kawawa naman,

for his mother

who lived in the States.

bed where I would hide with my eyes closed

under the bed where

scared

him.

a nest

See, my cousin, I explained, was afraid

of snakes because my cousins kept telling him

to watch out. They strew his room once with snakes

while shrieking “Watch out!” to his face so I can’t

really say he was gullible. They were fake,

but he ran from their house to ours where we,

too, had shoveled a den for plastic snakes.

So awful, I know, but it’s okay if you

want to laugh. We cousins turned out okay.

and my friend couldn’t tell

if it was appropriate to laugh

whether to laugh along with me, or

Maybe he was gullible,

but with snakes

and yelled “Watch out!” at his face.

hallway to his room

Watch out when you lock the door

behind you, watch out when you walk home alone.

Watch out!, they said to his face

bathroom

door

,

the they said to his face,

When he biked to our house,

when he played G.I. Joe’s

was gullible.

On a visit home after falling in love,

I was what you might call, in love,

corresponding thrice a day

I would’ve said what was true

And what wasn’t, but I’d already said too much.

Jane Wong

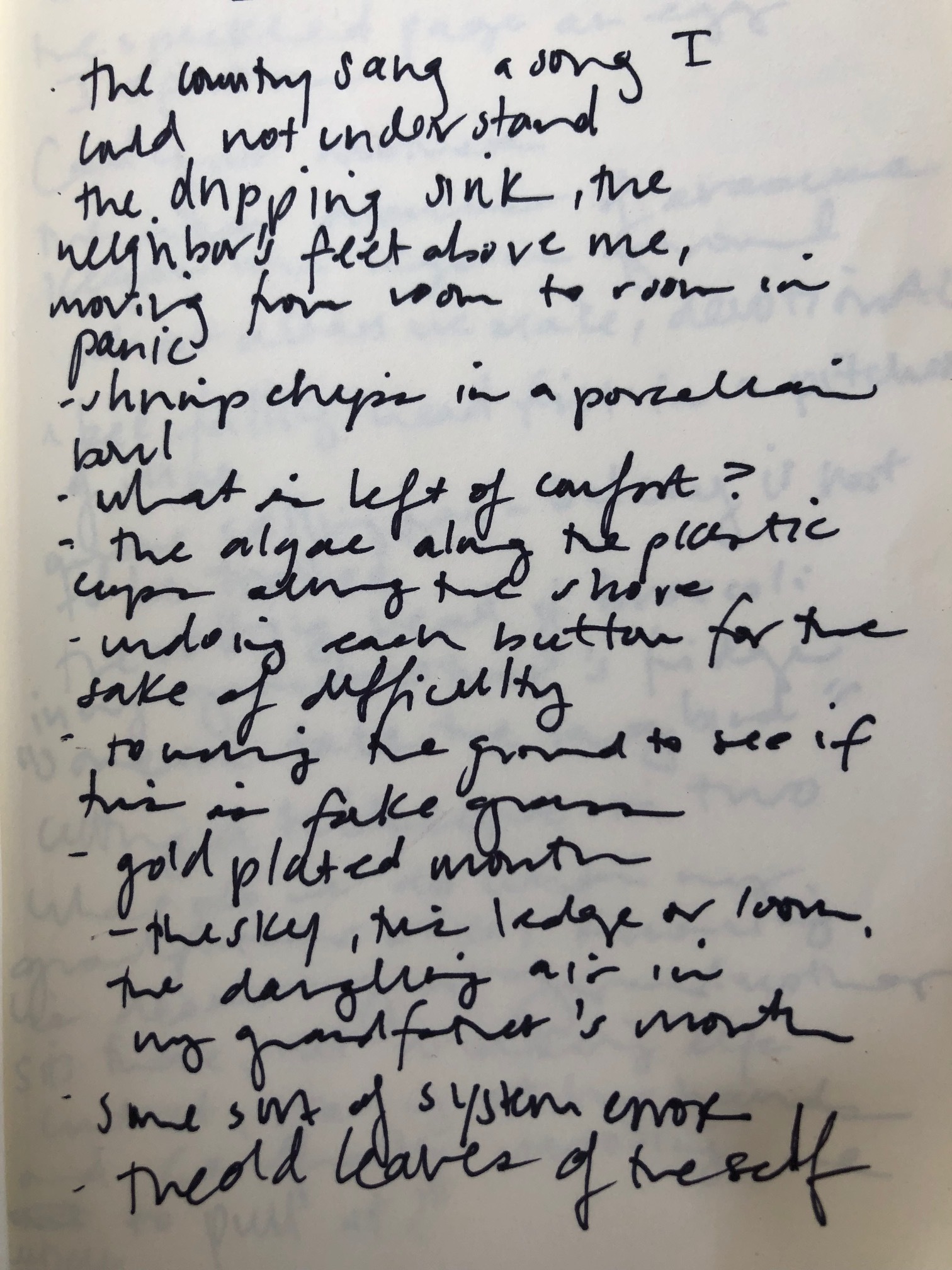

My poems always start from notes. I went on a kind of a scavenger hunt through notebooks. What I found from my notebooks: "someone in the apartment next door thrashes their furniture," an image of ants, "the dripping sink, the neighbor's feet above me," and then this thing I wrote: "Dear American Dream, eat roses, eat rats, eat a piece of garbage. Eat a rusted car tire."

All of these ideas swirled into my head as I wrote. I remember this poem being a heartbreak poem. And how everyone around me kept saying: "Well, at least there's something to learn from every heartbreak." I remember thinking: what is there to learn? Should I learn to be more pleasant, more polite? Less "intense"? And I ended with this poem here --- which strangely goes back in time and asks: what can I learn from the wisdom of my younger self? What can I learn from my family's experience with heartbreak (my parents' arranged marriage, the American Dream)?

The answer, by the end, seems to be clear: I must remain myself. Do not lessen, do not be swayed by false promises.

Also, in revision, I've started recording myself and revising after listening to the play-back. Something about hearing my voice/the breath helps. You can see that via the stanza breaks.

*

The poem originally appeared in The Adroit Journal.

lessons on lessening

I wake to the sound of my neighbors upstairs as if they are bowling.

And maybe they are, all pins and love fallen over.

I lay against my floor, if only to feel that kind of affection.

What I’ve learned, time and again:

Get up. You can not have what they have.

And the eyes of a dead rat can’t say anything.

In Jersey, the sink breaks and my mother keeps a bucket

underneath to save water for laundry.

A trickle of water is no joke. I’ve learned that.

Neither is my father, wielding a knife in starlight.

I was taught that everything and everyone is self-made.

That you can make a window out of anything if you want.

This is why I froze insects. To see if they will come back to life.

How I began to see each day: the sluice of wings.

Get up. The ants pouring out of the sink, onto my arms in dish heavy water.

My arms: branches. A swarm I didn’t ask for.

No one told me I’d have to learn to be polite.

To let myself be consumed for what I can not control.

I must return to my younger self. To wearing my life

like heavy wool, weaved in my own weight.

To pretend not to know when the debtors come to collect.

return to twelve

I wake to the sound of my neighbors upstairs as if they are bowling.

And maybe they are, all pins and love fallen over.

I lay against my floor, if only to feel that kind of affection.

What I’ve learned, time and again:

Get up. You can not have what they have.

And the eyes of a dead rat can’t say anything.

In Jersey, the sink breaks and my mother keeps a bucket

underneath to save water for laundry.

A trickle of water is no joke. I’ve learned that.

Neither is my father, wielding a knife in starlight.

I was taught that everything and everyone is self-made.

That you can make a window out of anything if you want.

This is why I froze insects. To see if they will come back to life.

What is made and un-made.

And yet, each morning, the starting out, the ants pouring out

of the sink, onto my arms in dish water.

My arms: branches. A swarm I didn’t ask for.

No one told me I’d have to learn to be polite, to let myself be consumed.

I must return to my younger self.

To wearing my life like heavy wool,

weaved in myself. And when debtors come to collect,

I will pretend not to know.

Keith S. Wilson

I don't always love sharing old work. Not because I'm ashamed of its quality (that's not a feeling I enjoy, but I can move past it), but because when you write anything, you embed your ignorance and prejudices into your work. Of course, this shows in your finished pieces as well, but by then you've had a chance to examine yourself and your work, and have had the ability to perhaps do some change. An early draft can expose potentially hurtful or oppressive language—thoughts that were unconscious and demand reexamination, sentences in which you didn’t know what you were even trying to say, and lines that contain ambiguities that allow for readings you don’t believe in. Language can put others at risk, and I think it's important to try to consider that risk.

Everything I write begins as a free write. I wanted “scrapbook” to be about American violence, and I wanted to do it in fragments, the way Sappho's recovered works appear, since time itself is a kind of destructive force. I named it, originally, "frags," because of the fragmentary nature of Sappho's work as we know it and the association with fragmentation grenades. At Vermont Studio Center, where I had access to a corkboard, I cut the poem into pieces and rearranged them. But the poem had evolved in my mind to be more about implied violence and masculinity and power. I worked in new scraps (highlighted in yellow), each taken from separate poems about totally different topics. The starred stanzas, short as they are, are poems in their entirety (in order from top to bottom, they are titled: “sextant,” “title,” and “parable.”)

The sextant section changed because whatever story I had been trying to tell could never be as loud as my being a man telling a woman her own feelings: “you thought a moment...” That became especially evident when it was re-contextualized in a poem specifically about this kind of assumed power. As uncomfortable as it was in this case, I would rather embody the man. I also changed the Sisyphus section, which in earlier versions felt to me as focused a lot on the dress. I couldn't decide what that meant, precisely, but it seemed to mean something concerning gender expression—that people who express themselves in what is considered non-masculine attire are saddled with the responsibility of men's actions. I wanted to allow for that read, but not position it as the only way to interpret that section.

I felt uneasy with what I was trying to say in scrapbook (or rather, whether I was saying it) up until the night before it was published—and asked close friends to read it, and read it myself, and sent late night edits to the editor. Maybe I still worry. Privilege is power, and some forms of privilege cannot be put down, no matter the effort to do so. Writing a poem like this can feel like gesticulating passionately with a gun about all the firearms in a room in which some of the people are holding guns, all the while hoping mine doesn’t go off. The alternative feels like merely holding it—deadly quiet—in my hand.

*

This poem was first published in Triquarterly.

SCRAPBOOK

after ladan osman

i. look—in the middle distance the siren screams

like a fatherless boy,

unashamed. ii. sisyphus hikes up her dress.

she labors pushing,

always a man,

and if she shrugs, he rolls atop her

or the town at the foot of the hill. or a man, calling himself sisyphus, knocks

and says: push is a man’s verb

but she can help. or else,

he says, quiet. iii. it’s said we are afraid

of what we don’t understand. who

among us is shaken by latin? we are terrified of what might

overtake us. sadness, marriage, spanish,

rain. iv. like a sextant he angled himself as if

(as if!) to kiss. his hands in the ocean of her

eyes and his knee pressed against the air

like a rudder. v. how can i make you

understand? as a boy i held a bell in my hand. and i grew

to be a man who looks back

on that bell. vi. what is there

to say? that was yesterday. vii. the first thing odysseus decides

when he returns is to cock his bow. fire

in the crowd. over and again, bullets move

at flirtatious angles. viii. in the city, the first november rain

laps at a set of heels. ix. a family of plantains.

no one speaks

their name. actually,

a silence, even when they are perfect and brown.

every domestic, familiar,

unpretty thing. x. i’ll say it again:

if a hand is big enough it doesn’t matter

what you call it. xi. the story of orpheus and the bear is this—

orpheus, of course,

sings. his wife is distinguished

by her marriedness

to orpheus. jumping ahead: he left behind his clothing, his furniture

and everything. xii. there is an old story

of a man. that is the story.

there is an old story of a woman

that the old story of the man spoke over.

i am his son. xiii. imagine here the voice

of a woman. xiv. a list of all that is fixed:

only the ground.